The gay imam: a desperate and hopeful story at the same time

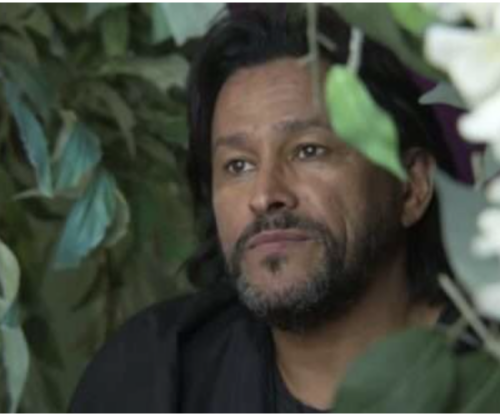

Muhsin Hendricks was the first openly gay imam. For twenty-five years he was the soul, the mentor, the defender of queer African Muslims. He was killed in an ambush in Cape Town on 15 February.

His is a story at once despairing and hopeful.

‘God is not homophobic,’ he said. ‘Nobody has a monopoly on religion,’ he added. And he fought homophobia with the Koran.

In Italy, Muhsin Hendricks has not been mentioned at all. Here, in my blog Branchie, on ReWriters Magazine, I tell his life story, show the video of his murder and interview Shenilla Mohamed, Executive Director of Amnesty International South Africa, on the situation of queer people in Africa and human rights defenders in general.

Who will continue the work of gay Imam Muhsin Hendricks after his murder?

The LGBTQ+ community that gathered around Imam Muhsin Hendrix is in grief and panic after the murder of its founder. Interview with Shenilla Mohamed, director of Amnesty South Africa.

Muhsin Hendricks was the first openly gay imam. For twenty-five years he was the soul, the mentor, the defender of queer African Muslims. He was killed in an ambush in Cape Town on 15 February.

I knew that asking Shenilla Mohamed, Executive Director of Amnesty International South Africa, to speak about this would be to delve into a personal grief as well: Muhsin was for her not only one of the bravest and clearest defenders of human rights in her region, but also a dear friend, a valued and beloved friend.

Muhsin Hendricks

Born in Cape Town in 1967, Muhsin – Indian and Indonesian ancestors brought to South Africa as slaves by the Dutch colonisers – had grown up in a family of strict Islamic orthodoxy. Already at the age of five, he had realised that he did not fit into the gender mainstream; later, as a teenager, he was sure of it: he was not a ‘good Muslim’, he was a man attracted to other men: one of those homosexuals against whom his grandfather the Imam used to lash out in Friday sermons, foreshadowing the wrath of Allah on their heads, which would lead them to hell, if not first to a just and terrible punishment in life. Therefore, Muhsin had married at some point. He had tried to walk the path they showed him in the mosque. He was 24 years old, handsome as an actor. His very young wife was very much in love with him: but seven days before the wedding he had not felt like deceiving her and had told her about his loves. The marriage had however lasted six years, they had had three children.

In 1996, Muhsin got divorced and fled to Pakistan, where he had done his university studies in Koranic Law. A friend offers to put him up in a stable by turning out the horses, and there Muhsin fasts, prays and meditates for 80 days. Until he spots a red thread and, following it, realises that he is finally at ease in his relationship with God, Islam and himself.

When he returned to Cape Town he came out (the hardest thing was to tell his mother) and founded a community, The Inner Circle, where those living in the pain and trauma of not seeing their faith in Allah reconciled with their homosexuality find refuge and dialogue.

‘God is not homophobic’

‘God is not homophobic,’ said Muhsin. And he fought homophobia with the Koran.

Because a compassionate God cannot condemn people he has created in this way, for whom sexuality is not a choice but a fact, he explained. And he added: ‘No one has a monopoly on religion’.

In 2007, the local Muslim Judicial Council declared him ‘out of the fold’ of Islam for appearing in the documentary “Jihad for Love”. In 2011 he marries a man (South African law has allowed this since 2006). In 2022, he is the protagonist of “The Radical”, which recounts his urgent and unwavering faith and his religious and social activism. From the documentary, there emerges a compassionate and reconciled personality with the world, around whom he always managed to form an oasis of peace, understanding, even cheerfulness.

The word imam means guide: and Muhsin was the leader of a community of marginalised people who asked him to understand them, protect them and advance their cause. Muhsin offered them new words, reinterpreting sacred texts in the light of a theology that centred on the idea of a compassionate God, capable of welcoming love in all its forms. ‘God did not create us to condemn us,’ he often repeated. And that statement, in a context where scripture is often used – in the same way as in other religions – as an instrument of oppression, was a revolutionary act.

‘I am not afraid of death, I am more afraid of not being myself’.

He was subjected to heavy insults and death threats, in a country that has one of the highest rates of violence in the world. Asked if he was afraid, Muhsin replied with his unmistakable sweet yet witty smile: ‘I am more afraid of not being myself than of death. I lived for too long in the state of one who hides himself, I only found serenity and balance, and also the joy of living, when I was able to connect my identity with my faith in Allah. And with that, I also found happiness in being able to help others.’

He exposed himself. He talked to everyone. They say he was killed on his way home after celebrating an interfaith marriage, not approved by the most orthodox Islam. But there is no certain confirmation of this. The police to date have not indicated any leads, they continue to state that they do not know the reasons for his murder.

The pain and fear of the LGBTQ+ community

Right now his LGBTQ+ community is locked in pain and fear. The website of Al-Ghurbaah Foundation, the foundation with which Muhsin held meetings, prayers, courses and seminars in the field of what the international press has hastily called queer theology, is ‘temporarily unreachable’. On Saturday 8 March, during the iftar of Ramadan, a ceremony was held to commemorate Muhsin in the Open Mosque in Cape Town (an inclusive mosque that believes in cultural exchange and women’s equality, open to all as its name implies, but which holds on its site today to mark an institutional distance from the gay community). ‘I had great respect for him and what he did, it was really amazing for Islam. He proposed a kind of new focus on Islam. He wanted – and I fully agree – an Islam focused on compassion,’ said the Mosque president. But more than half of the chairs were empty, and neither Muhsin’s family nor members of his community, who had been expressly invited to attend, were to be seen.

With Shenilla Mohamed (who also shares with Muhsin the fact that she grew up in a rigidly orthodox religious context, as well as the love for Pakistan – where she was born – and the fact that they both speak Urdu) I will leave aside the questions I would like to ask her about her personal relationship with Muhsin.

Shenilla, I know you called for special legislation to protect human rights defenders in your region, what exactly do you mean?

Human rights defenders in South Africa continually face challenges to their work – threats, intimidation, killings, unfair prosecutions and cyberbullying – including from institutions. They often do not denounce for fear of reprisals. South Africa has no specific legislation or public policy for the protection of human rights defenders and the authorities have never created an instrument to record the number of threats and attacks against them. The responsibility for repressing these attacks lies with the State. As Amnesty International South Africa, we call on the South African government and President Cyril Ramaphosa to recognise human rights defenders and their work, and to commit to developing and adopting national legislation for their protection by the end of 2025.

Yet South Africa’s post-apartheid Constitution is one of the most liberal and progressive in the world, rests on the country’s past suffering and a solid body of law. How is it possible that its principles are so easily overwhelmed?

As a nation with a history of apartheid, South Africa continues to struggle with racism in in all its forms, but members of the LGBTQ+ community still face discrimination and oppression. The country continues to face high levels of gender-based violence, caused by inequality of power between the sexes and deeply entrenched patriarchal norms, attitudes and beliefs. These social factors enable and perpetuate violence despite the constitutional protections in place.

The challenge in fact lies not in the legislation itself but in its implementation, in the inability of the state to hold perpetrators accountable. The extrajudicial executions make it clear how urgent the need is to enforce the rule of law. To uphold the principles of the Constitution, it is crucial that the perpetrators of these crimes are held accountable and face justice through effective, efficient and fair trials.

Muhsin had also travelled to Kenya in recent years to help the LGBTQ+ community oppressed by an anti-homosexuality law. Who is fighting now in Africa for the queer communities and with what tools at their disposal and what consensus among the population?

Recent years have seen a surge in discriminatory legislation against LGBTQ+ people across Africa. In 2024, Amnesty International published a briefing paper on 12 African countries, documenting how legal systems have been increasingly used to systematically target and discriminate against LGBTQ+ people. This paper includes cases where laws have been blatantly used to persecute and marginalise members of the LGBTQ+ community, highlighting a distressing trend of using legal mechanisms as tools of oppression. In Africa, 31 countries still criminalise consensual same-sex sexual activity, despite the fact that this is contrary to standards set by the African Union and international human rights.

Will justice be obtained for Muhsin?

We have demanded and continue to demand, for every case like this, a swift, effective and thorough investigation into the murder. The criminal justice system must hold the perpetrator accountable and act as a deterrent against such horrific crimes.